How basic income benefited Irish artists

Ireland introduced a basic income scheme for artists. It had huge benefits for their art, their mental health, and the economy.

Written by Jack McGovan / Edited by Libby Langhorn

When artist Áine Ryan saw a scheme in 2022 offering artists a monthly stipend over three years, she thought it was too good to be true. She’d just graduated from Art College Crawford in Cork, Ireland, as a mature student the year before and decided to apply despite it seeming like a bit of a pipe dream. “That's what you do when you're out of college—you kind of apply for everything,” she said.

After just finishing a residency at the National Sculpture Factory in September 2022, Ryan received an email telling her she’d been accepted into the Basic Income for Artists (BIA) scheme. Even then, she struggled to get used to the idea that she’d have this reliable source of income. “It took about a year for me to be confident that nobody was taking the money away,” she said.

Ryan is one of the 2000 artists—including visual artists, writers, and musicians, among other professions—selected through a lottery system to receive the BIA. Since September 2022, she’s been paid the equivalent of 325 euros per week in monthly instalments. The aim of the scheme was to address longstanding challenges in the arts sector like low and unstable earnings, limited job security, and artist wellbeing.

A report on the scheme was published in September, with results showing that for every euro of public money invested in the scheme, there was a 1.39 euro benefit to the economy. Unsurprisingly, a modicum of financial security led to lower feelings of anxiety or depression for the participants by 13 and 11 percentage points respectively. Whether correlation or causation, the artists were more likely to complete new works and participate in exhibitions, performances, or other audience-facing activities by 10 percentage points.

Another basic income scheme for creatives, though much smaller, found that the artists who received the money improved the quality of their work, their life, and advanced their careers. A five-year scheme for low and mid-income residents of Hudson, USA, found that a basic income improved the mental-wellbeing of participants and allowed them to pursue further education or career opportunities.

Ryan, whose work focuses on glass, used the money for materials, for exhibitions, for travel, and for sending her work abroad. Thanks to the BIA, she was able to attend a four-month residency in the UK, which led to further opportunities: “If I was working part-time or full-time, could I get a weekend off to go with my work, to set it up, and be there for the exhibition opening? Probably not.”

All of the artists who spoke to Sower said the money they received gave them more of an opportunity to focus on their art. Whereas for most that meant being able to give up jobs like teaching art to others, for visual artist Jane Hayes it meant that she was able to afford childcare, which she said is difficult to get in Ireland in a manner that fits the sporadic nature of arts funding.

With a secure chunk of money coming in, she was able to plan ahead and dedicate the BIA to childcare and a studio. That, in turn, provided her with the space she needed to apply for funding for her art. “I’ve got steady public funding ever since because I've been able to keep on top of applying,” she said.

Hayes’ work focuses on gallery-based art for children under six, informed by her own experiences as a mother. She has received multiple awards for her work since receiving the basic income and has said that the money she invested into her art has finally started paying off. “It's so difficult for an artist to get that starting foundation that you need to have the snowball effect,” she said.

The BIA report found that average earnings in the Arts and Entertainment sector in Ireland were 20.4 euros an hour, significantly less than the national average of 27.7 euros an hour. The majority of Irish artists, 54 percent, were self-employed in 2022, meaning they wouldn’t receive the additional benefits that traditionally employed people do, like sick pay and paid holidays.

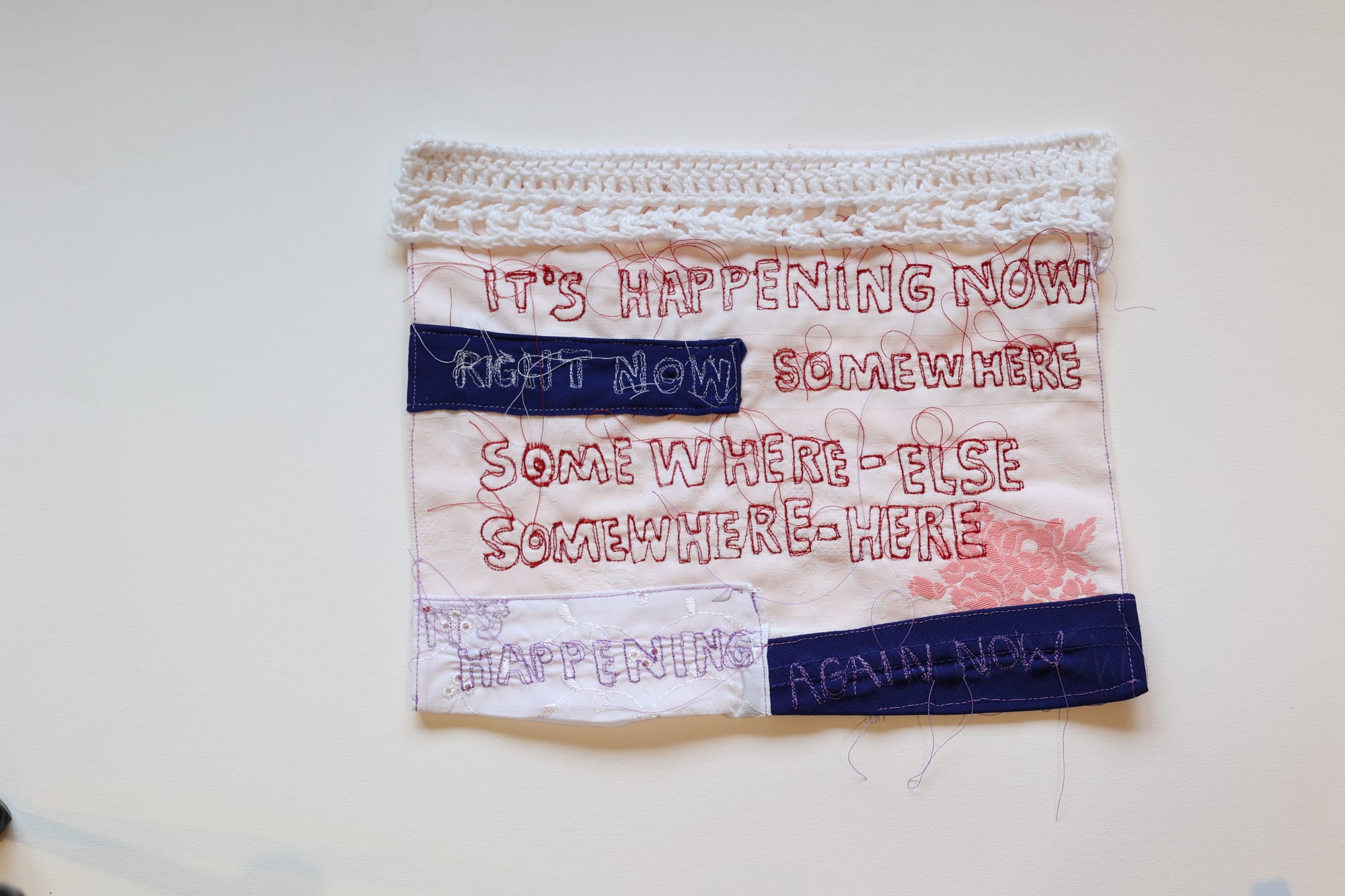

Many artists involved in the scheme have struggled to receive funding or recognition through traditional avenues. Christina Bennett, an artist working with film and textiles, feels like receiving the BIA was an acknowledgement that she was actually an artist. “I've spent years applying for Arts Council grants, which I've never been successful in receiving,” she said.

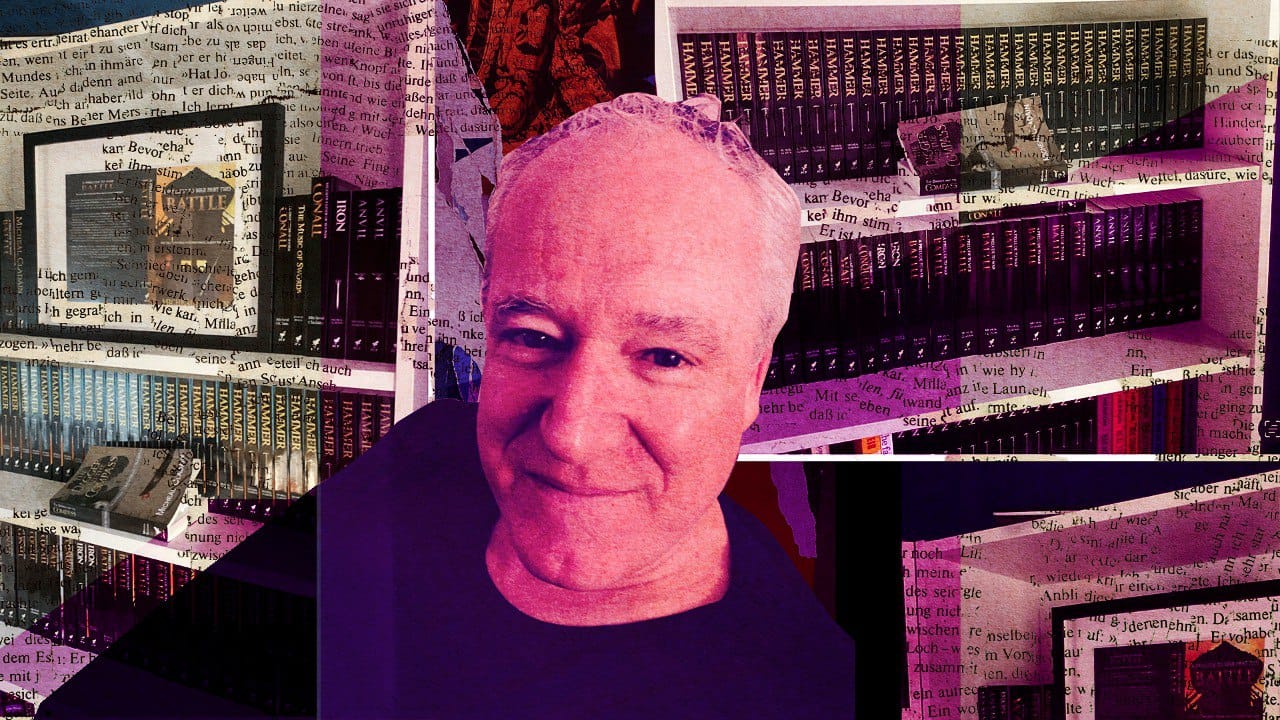

Before writer Phil Hughes received the BIA, he’d spent six years working full-time on his creative writing after being made redundant as a technical writer for a big multinational in the IT industry and still being able to rely on his wife's income. However, he’d been unsuccessful at breaking into traditional publishing with his fantasy, crime noir, and historical novels. “The fact you can't get published is a huge cross to bear,” he said, adding that the basic income helped make him feel like less of an imposter.

Accessibility more generally is one of the potential major benefits of a BIA. Queer, disabled, and racialised minorities regularly face discrimination in the Irish arts sector, and lose opportunities on the basis of their identities. By providing a basic income to people in these communities, they’d be less reliant on institutional support to develop their work. “The arts have always been much easier to pursue if you come from money, privilege, or stability,” said writer Katie McDermott in an email to Sower.

McDermott used the money from the BIA to take more risks with her writing by experimenting with novels, flash fiction, and non-fiction. Still, she highlighted that she was in the privileged position to do so, as her husband has a stable income. One critique she had of the scheme was that disabled people who took the money would lose their disability benefits. “There is a push for diverse voices in the arts, but the financial support needed to encourage that diversity has been lacking,” she said.

Another critique of the scheme came from Hughes, who felt like it should have been specifically targeted at full-time creatives—or people who wanted to go in that direction—and not those in full-time employment. The limiting factor for those in full-time employment working on their art would be time not money, he said, so the basic income wouldn't help them, and they’d end up having to pay a decent chunk of it back in taxes.

One person told Sower that artists should get social welfare credits towards their pension on the basic income, and a few mentioned that bi-monthly payments would be more helpful than monthly. When the report for the BIA scheme was published, it was also announced that the scheme would be made permanent. However, questions remain on how it will be rolled out or how expansive it might end up being, with some artists who received the BIA now concerned about the future.

“I'm frantically trying to make myself viable financially before March kicks in because we don't know what's happening,” said Darren Cassidy, an artist working with ceramics. While it’s important to be aware of the economics of art, Cassidy believes the true value lies in the therapeutic benefits of art—both for the artist and the viewer.

An overwhelmingly majority of both the Irish general public and artist community, 97 percent, said they supported the introduction of a permanent BIA in a poll that received 17,000 responses. The majority of people, 47 percent, thought those receiving the basic income should be in economic need, whereas 37.5 percent favoured selection based on artistic merit. Only 14 percent preferred the lottery system currently used.

Although the implementation of a lottery system for the BIA was somewhat controversial, Bennett liked it because she felt that if she had to write a proposal and state her case, she isn’t sure that she’d have gotten it. The BIA, she said, made it easier for people who aren’t good at writing grant proposals to get access to funding and develop their practice.

Cassidy had mixed feelings about the lottery system, in that he sees some value in having to justify why you should receive the money, but at the same time he doesn't think that unproven artists—like young people—should be excluded. "You have to make sure then the people that are doing it are dedicated to what they're doing," he said.

In a blog post published in July, writer Oisín McGann made the argument that a basic income specifically for artists is the ideal stepping stone for a broader universal basic income. He wrote that artists are defined by their work and so typical criticisms of a basic income—that people will no longer work—are negated. Research suggests that targeted, short-term schemes could be better for proving the long-term efficacy of a basic income.

Regarding the poll, there's also a question of what constitutes artistic merit and who gets to decide that. Although he's from the UK, musician Sam Fender has talked publicly about how the music industry is "rigged" in favour of the privately wealthy. If proven success is the metric on which people are judged to receive a basic income, then in that example the basic income would go predominantly to people who are already wealthy.

In a world of instant gratification—a world where people have asked him if his ceramics are made by AI—Cassidy said that art is more important than ever. Art, however, takes time to develop and the people making it need support. "Now more than anything is a time to support artists," he said.

That’s along the lines of how Bennett views things as well—if you don’t support people to immerse themselves in the creativity industries, the well of talented people will run dry. “Our natural resource is the Irish psyche, really,” she said. “We've always punched above our weight in terms of writers, film, and you know more increasingly we're showing our strengths as visual artists.”

Ryan thinks the true benefits of the BIA will show up years down the line, when you’ll see Irish artists being appreciated by awards like The Booker Prize or Mercury Music Prize: “When you have more people from one country being creative in whatever way that is—music, writing, visual arts, film, whatever—you're going to find gems there that otherwise wouldn’t have been found.”

Comments ()