Can eco-populism help defeat the far right?

Written by Jack McGovan / Edited by Ruxandra Grecu & Libby Langhorn

When Zack Polanski launched a leadership bid for the Green Party of England and Wales in May on a platform of eco-populism—aiming to create a home for those who care about environmental, racial, social, and economic justice—the party had its second largest membership growth of any month on record. The people are hungry for change, and my stomach, too, is rumbling.

Wildfires are burning through the biosphere in the same way that “AI” slop is drowning our information ecosystems, while prices continue to rocket for everyday people and billionaires amass wealth like tumours stockpiling cells. Rather than dealing with any of that, politicians have instead chosen to police genitals in toilets and give into moral panics about cultures that know how to spice food.

Rhetorically, the far right have their unwashed fingers in way too many pies globally. Mainstream politicians in countries like the UK, the USA, and Germany have adopted and normalised rightwing talking points on a range of issues like trans rights and immigration. The far right’s refusal to acknowledge humanity’s impact on the planet means they're a one-way ticket to stronger wildfires, more destructive floods, and catastrophic crop failures.

Polanski’s eco-populist platform, should he win the ongoing leadership election, is about building a counter-narrative for the future that reduces inequality, makes society more sustainable, and proudly speaks up in defence of the marginalised—it’s the billionaires and yachts that are the problem, not the dolls or dinghies. “The same system that is poisoning our rivers is poisoning our minds,” he said in a promotional video for his leadership campaign shared online.

It’s a message that seems to offer a real alternative to fascism, unlike the tepid centrism that has ruled for the majority of my life. However, the last attempt to steer the UK into a better future was crushed after the bitter defeat of Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party in 2019. Does Polanski’s vision of eco-populism—or green economic populism as it’s otherwise known—have the power to triumph where other leftist projects have failed?

“Green economic populism is effectively the notion that economic policy should be used for the benefit of working people, and it should be done in a way that addresses the climate and broader ecological crisis that we face simultaneously,” said Patrick Bigger, research director at progressive think tank the Climate and Community Institute, USA.

Interventions that fall under green economic populism include state investments in renewable energy production or infrastructure that would lower people’s bills, creating jobs in the production of batteries for electric vehicles or public transport, and investments in the kinds of work that are low carbon and benefit society, like care work, said Bigger.

When asked about issues affecting them personally, people from the UK said they were most concerned about the rising cost of living.

He added that we can often get hung up thinking about molecules and other abstract concepts when it comes to climate policy. Instead, eco-populism should refocus climate action in a way that gives people something to point to and say that it has improved their lives—by, for example, reducing their bills or providing them with meaningful employment. “Good climate policy is climate policy you can touch,” he said.

Americans listed the affordability of healthcare, inflation, and the number of people living in poverty noticeably higher than immigration on a poll of national concerns earlier this year. European youths said they were most concerned about rising prices and the cost of living, and when asked about issues affecting them personally, people from the UK also said they were most concerned about the rising cost of living. Clearly there’s a gap in the rhetorical market for policies that make people’s lives easier.

Climate policies don't necessarily have to be communicated as such in order to be effective either, and there are a number of examples demonstrating so in the US. A fare-free bus pilot in New York City saw 11% of riders choosing the bus over their usual car or taxi ride, leading to a reduction in emissions. Zohran Mamdani, who won the primary to become the Democratic mayoral candidate for NYC in June, has promised to expand fare-free bus rides across the entire city on affordability grounds as part of his platform.

In July 2022, the Whole-Homes Repair Program was created as part of Pennsylvania’s state budget. Introduced by state senator Nikil Saval, the programme provides grants for low- and moderate-income homeowners to undertake critical home repairs, job training for careers in home retrofitting with cash stipends for trainees, and support staff to help eligible applicants access the correct programmes.

Saval highlighted one instance of a single mother with two children who applied for funding through the programme due to a lack of heating in her home. She had a heat pump installed and repairs done to her kitchen floor and roof, soon to be equipped with a solar array. “There are lots and lots of stories like this—people who are able to stay in their homes who otherwise might have lost them,” said Saval.

"Good climate policy is climate policy you can touch" – Patrick Bigger, Climate and Community Institute

The New York Public Renewables Act, passed in 2023, mandates that the New York Power Authority (NYPA)—the largest state public power organisation in the USA—should help to meet climate goals by building publicly-owned renewable energy wherever the private market falls short. A key part of the campaign was dispelling the popular myth that climate action is in opposition to people’s jobs.

“We knew that we needed to pass something that created really good jobs for working people across the state and really kind of reframe and redirect the conversation so that it is, you know, jobs because of climate,” said Patrick Robbins, organiser at Public Power NY and one of the people behind the campaign.

Part of developing the bill, eco-populist in nature, meant thinking about how to protect vulnerable communities. In New York, Robbins said, there are methane-fired peak power plants in low-income, black and brown communities—an environmental injustice which leads to higher rates of asthma. Finding a way to replace some of that dirty energy generation was key to the campaign.

The environmental movement is often criticised for not taking into account the needs of marginalised communities. In the UK, for example, people of colour are four times more likely to live in areas at a higher risk of heatwaves, and queer people constitute a disproportionate number of the homeless population, making them more vulnerable to extreme weather events. Climate action is inherently linked to the politics of social justice, and no community can be left behind.

“We developed the bill and developed the legal language of the bill through an extremely- and, at times, maddeningly-thorough democratic process,” said Robbins. They added that they and their colleagues spent time interviewing different groups and getting feedback for well over a year. “I don't think there should be any shortcut or any substitute to that process.”

Senator Saval hopes the Whole-Homes Repair Program could open people’s eyes to how the government could improve their lives. However, he’s not necessarily convinced that isolated policies, no matter how good they are, are enough to shift people away from the political right. There needs to be a broader narrative coalesced around an enemy like fossil fuel companies or billionaires, he believes, for eco-populism to be successful.

I do think, however, that offering a positive vision of the future is equally as important as having an opponent to rally against. Let’s take down billionaires not only because they’re sociopathic ghouls, but because their wealth belongs to us anyway, as it is upon our collective labour that their fortunes are built. With our reclaimed wealth, we could retrofit people’s homes, create secure jobs in the expansion of publicly-owned renewables, and invest in free education so people can retrain at any age into jobs fit for the future—or study something purely out of interest or obsession.

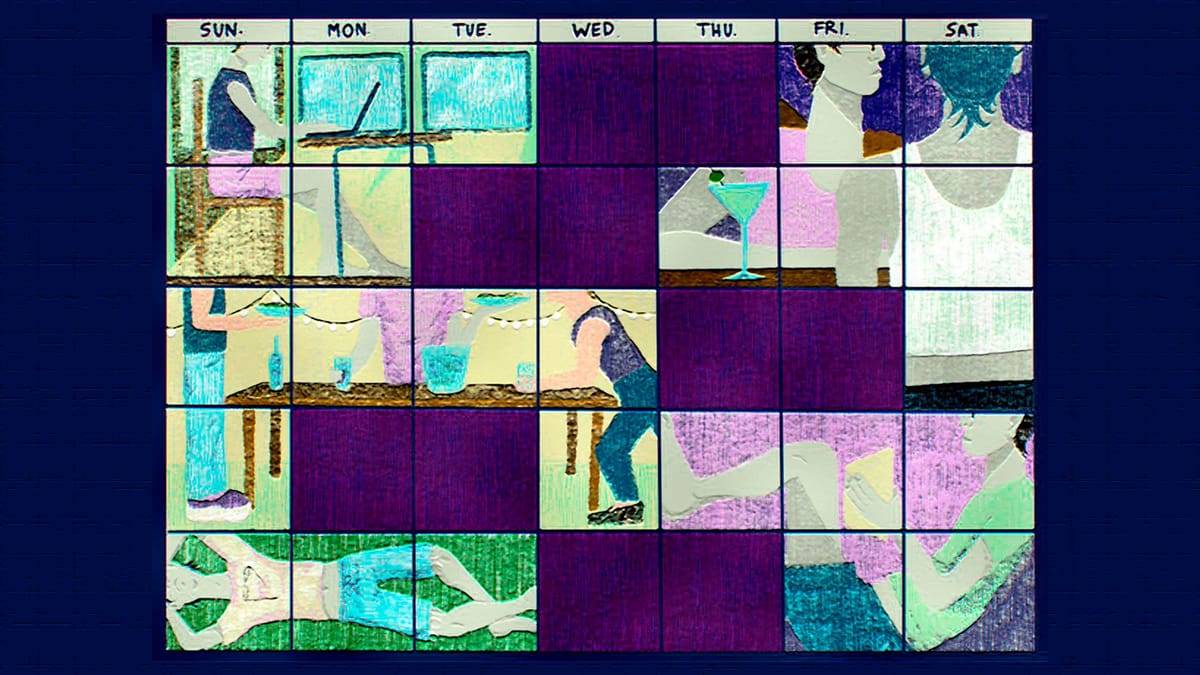

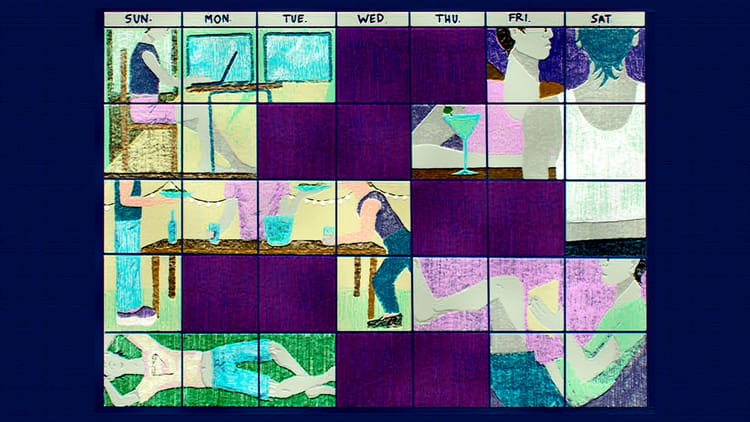

Productivity gains have been unprecedented in recent decades due to automation, and those gains should be redistributed as a four-day week for everybody instead of lining shareholder pockets. An extra day of freedom would mean spending more time with our loved ones and give us more chances to engage with our communities, fostering a collective spirit in our local areas. With people more in tune with the needs of their neighbours, we could restore local economies and shift towards public transport, leaving children free to explore without fear of being flattened by an SUV.

Polanski’s messaging so far has identified an enemy, but his website offers no insight into specific policies his brand of eco-populism might offer, nor did his team respond to my request for comment. Even if he does everything perfectly, however, recent history has shown us that the sheer might of the right can be used to destroy and dismantle well-meaning political projects. Not everyone necessarily agrees, either, that Polanski’s approach is the best way forward.

The day after the Brexit referendum is seared into my brain. Whether it was the terrible news or the CBD that made me sluggish, I’m still not sure. Me and a friend exchanged the joint more frequently than words, the smoke around us a manifestation of the dark cloud that had happened upon our lives. My back pressed against the cold concrete wall, an on-the-nose metaphor for how I was feeling. As two English twinks living in the Netherlands, our lives were about to change.

A little dramatic, perhaps, given that the impact on my life hasn't been as grand as initially imagined. What I can say, however, is that there’s been an underlying sense of unease in politics for me since that vote, though I, embarrassingly, didn’t have much of a political consciousness until then. Seeing how the right used misinformation and false narratives to achieve their aims—and get away with it—had awoken me to the reality of the world.

The infamous Breaking Point poster, published in the final week before the referendum, depicted a photograph of Syrian refugees at the Croatia-Slovenia border and implied it was a queue for entry into the UK. Similarly, the official Vote Leave bus stated we should give 350 million pounds every week to the National Health Service instead of the EU, something that never came into fruition. Dishonesty is a core principle of the right, an awarded virtue in our society.

During the 2024 election in the UK, Nigel Farage, leader of the far-right Reform party, was the third most covered politician despite neither him nor his party ever having won a seat at the time. “There's like this kind of fascination with the far right [in mainstream media] and that amplifies their visibility and message,” said Katy Brown, a research fellow at Manchester Metropolitan University who studies the mainstreaming of far-right narratives.

Brown highlighted that in the future she would like to work with media organisations and journalists to come up with guidelines for reporting on the far right. One key aspect she mentioned is that journalists shouldn’t just focus on how bad the far right are, but put their actions into the broader context by exposing how far-right talking points have been normalised by mainstream political parties.

During the 2024 election in the UK, Nigel Farage, leader of the far-right Reform party, was the third most covered politician despite neither him nor his party ever having won a seat at the time.

In order to tackle the far right, she suggested building a positive counter-narrative about the kind of society we actually want to build and doing so without shame or hesitation—eco-populism, essentially. “It's certainly not an easy task, because there's a lot of resistance to it from powerful voices,” she said.

That's why she’s not convinced that branding a left-wing movement as populist is helpful in the long term. She said that it creates the possibility for the mainstream to create a false equivalency between the left and the right and in the process claim that populists are a danger to society.

Aurelien Mondon, a professor of politics at the University of Bath who also studies the far right, agrees with Brown, as the word populism has been polluted by decades of misuse by anti-populists and moral panics around populism. “It was quite interesting to see Polanski trying to call himself a populist,” he said. “It seems to have worked fairly well so far, but we'll have to see what happens when he becomes a real threat [if and when he becomes leader].”

Although cautiously optimistic about the Polanski project, Mondon highlighted a few key points about how to properly fight the far right. He said that it’s important not to overstate the support they have, as even when they win elections it’s often with small a fraction of the vote; that the left shouldn’t be having them on their media platforms as all it does is normalise their views; and that we shouldn’t involve them in democratic debate at all.

“These people are not interested in discussion,” he said. “There's lots of debates we can have about how to fight racism, how to fight misogyny, [and] how to address the climate crisis, but [we] don't need a racist, a misogynist, or a climate denialist on the platform.”

Sian Cowman, a self-employed researcher whose PhD focused on climate migration and media discourse around it, said that while she very much welcomes eco-populist policies, she’s sceptical of a party’s ability to fulfil its vision under our current political and economic system. “My concern with all of these things… is that there's just a history of parties taking power and finding it very difficult to actually move forward,” she said.

Rather than focusing on a top-down approach where a political party takes power at a state level, Cowman believes we’d be better off organising locally. Examples she gave include building solutions like community gardens, energy projects, or resisting fossil fuel infrastructure.

When I think back to the defeat of the Corbyn project in December 2019, I remember a sense of hopelessness, echoing and compounding on that feeling I’d discovered in the aftermath of the Brexit vote. The left, tail tucked between its legs like a first boot on Drag Race, seemed defeated and fractured. Taking that scenario into account, I’m inclined to agree with Cowman that pinning all of our hopes for the future on a top-down political project might not be the most strategic choice.

While top-down political projects can mobilise massive amounts of people and resources and affect change in a way that local organising can't, the flipside is that they can flameout in a timespan reminiscent of a mayfly's life. Local communities, on the other hand, are a lot more resilient in the face of failure—more of which we'll almost certainly have to endure in the coming decades.

The Build Public Renewables Act was implemented without an overarching political project or figurehead, demonstrating that progress can happen with a bottom-up approach. Imagine where we could end up if groups in every city or state across the world worked to make a similar thing happen in their local area?

That doesn't mean we shouldn't try a top-down approach, too; the Whole-Homes Repair Program is a successful example of a politician taking power and doing something positive with it. I just think that the left can often be so focused on these grand political projects that, in some ways, reduce the burden of action to ticking a box in a voting booth every couple of years.

By building local connections instead, we can be sure that when somebody does make a dash for the halls of power, we have the underlying community infrastructure to support them and increase their odds of success. Even if they fail, we’d have still built a small prototype of the world we want to live in, a springboard we can practice on until the day comes when we finally stick the landing.

Want to make eco-populism a reality?

- You could see whether there are campaigns in your local area fighting for policies similar to the Build Public Renewables Act or the Whole-Homes Repair Program.

- If you're a member of the Green Party of England and Wales, you can vote for Zack Polanski in the ongoing leadership election. Otherwise, you could join the party or become an activist for them if he wins.

- Look into the politics of your local area/country and see if there are any people pushing for eco-populism—you could join their campaign and help support their project.

- Start organising in your local area—it doesn't have to be a group pushing for policy change, it could be anything from a community garden through to a reading group discussing relevant texts to theme of eco-populism.

- Share this article with people who might be inspired to act, and subscribe to spread ideas like this to a wider audience!

Member discussion