We spend too much time lionising people like Jane Goodall

Idolising people only entrenches the idea that it is spectacular individuals, not collectives, who change the world.

Written by Jack McGovan / Edited by Ruxandra Grecu

My hands have never been so saturated with sweat as the time I first picked up the phone to speak to somebody as a student reporter. A professor of mine had dazzled me with his charisma, rare in the chemical sciences, and success in the development of solar panels, so I decided to write about his life. Before I mustered up the courage to make the call, my boss encouraged me with one statement that I’ve sanitised for your reading pleasure: the professor goes to the toilet just like everybody else.

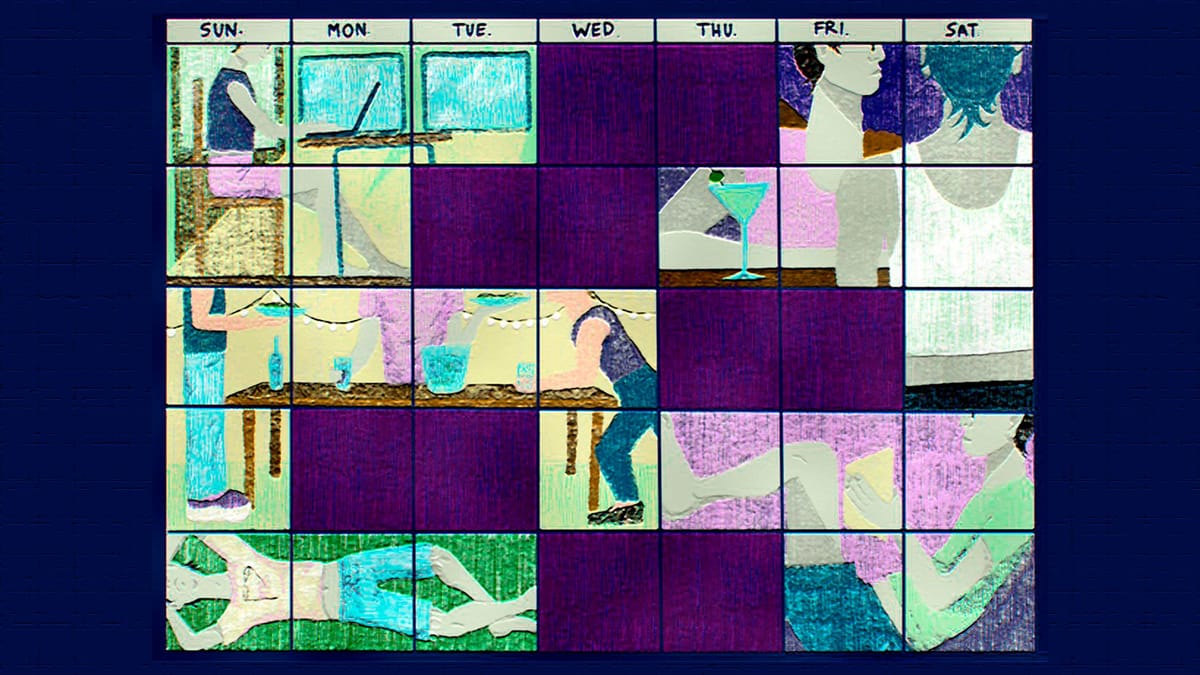

Although my admiration and interest in that professor dissipated over time, the statement has always stuck with me. Whenever I’ve felt the urge to put somebody on a pedestal, it’s helped ground me in the idea that they’re a human being just like me. When Jane Goodall died last week and social media exploded with all kinds of gushing obituaries, it got me thinking again of the dangers of idolising people.

Regardless of how you feel about Goodall, the one inescapable truth about her life’s work is that she wasn’t the only person responsible for it. I’m not trying to diminish anything about her tenacity as a pioneering female scientist at a time where gender equality was even worse than it is today, but it doesn’t make it any less true that her research was supported by a massive team of people (or that her parents being wealthy afforded her opportunities others did not have).

Not only does focusing on a figurehead erase the hard work of everybody else who contributed, many of whom would have almost certainly done more of the actual day-to-day work, it also pushes the broader narrative that it is spectacular individuals who are the driving force behind human advancement. As captured by mass-produced superhero movies, we’ve bought into the idea that special individuals will save us, not a broader collective.

The economic system we live under has nurtured these Great Man narratives because it’s precisely what keeps it propped up. Our system teaches us that those who work hard will rise to the top on the basis of their merit and contribution to the world. When we see people like Jane Goodall, a small part of us believes that we too can achieve as much as she has and rise to exalted status if we put our mind to it. Only by dangling that carrot before us does the neoliberal wheel keep turning.

Yet we don’t live in a meritocracy. In 2017, Kenyan conservationist Dr Mordecai Ogada published the book The Big Conservation Lie, which criticised “white saviours” like Goodall for contributing to the narrative that it is only through Western expertise that charismatic African species can be conserved and saved. Have any African conservationists received a damehood or regular well-paid speaking opportunities across the world for their work?

Goodall spent 300 days a year travelling to do advocacy work even up until her death, and flying so much undoubtedly made her a human being with one of the largest carbon footprints. However, she encouraged people to go vegan on environmental grounds, so she clearly believed that our consumption choices had an impact on the world. The only conclusion to be drawn from her excessive flying is that she believed her interventions were worth the carbon cost, that her presence at environmental conferences would help save the world from destruction.

That sort of thinking is replicated elsewhere. Climate scientists were found to fly more often for work than other researchers, presumably because they believe their expertise—their individual pearls of wisdom—are necessary to stop global temperatures rising. People who take to the skies more often are more likely to build larger networks that get them more recognition for their work, in turn providing them with more opportunities to be involved at conferences and other international events.

This creates a feedback loop where individuals are rewarded for prioritising their own success. I think that people in this feedback loop genuinely do care about the environment, it’s just that once their egos are inflated by recognition, stroking that ego becomes more important than the goals of the collective movement they represent. They want to save the world, but being the hero responsible for it takes precedence.

Many people await with bated breath this week to see who wins the different categories of this year's Nobel Prize, another example where individuals are awarded for the work of many. Oscars are typically given to those who build the most convincing campaigns, easier for those with excessive wealth, rather than those who produce the best work. Even in writing this essay I’m relying on the work and thinking of others who have come before me—my arguments would be less convincing without the links I’ve provided, for example.

All of this isn’t to say that we can’t recognise stellar achievements or that we bring nothing as individuals into our work and lives. We could instead move toward systems of recognition where broader collectives are rewarded for their contributions to a piece of work, something more akin to an acknowledgement section in a book. Until we move beyond the lionisation of individual humans, we will remain trapped in a world that values the success of the individual over the collective.

Comments ()