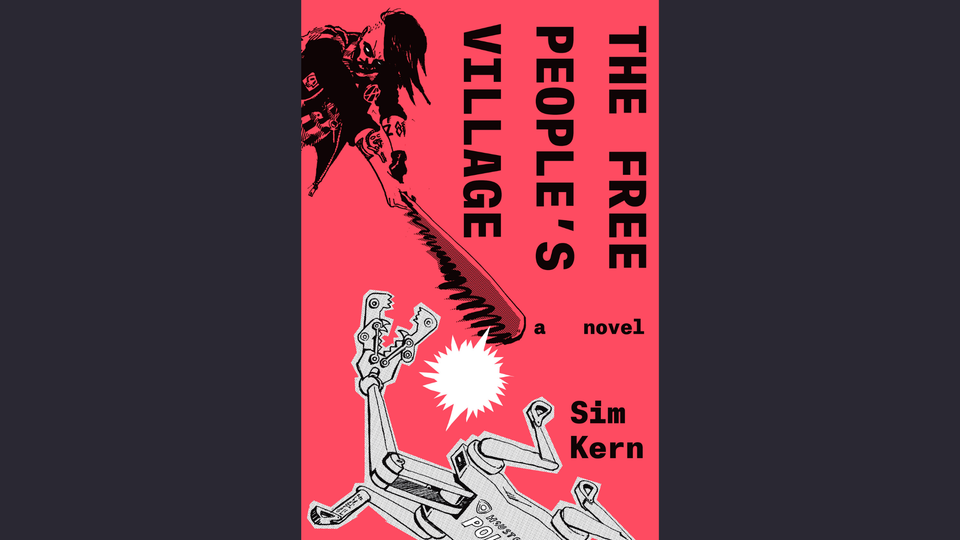

We have no choice but to find joy in the struggle for a better future

One of my favourite moments in Sim Kern’s The Free People’s Village is when Maddie, the protagonist, describes a shit-stained toilet—and I mean that earnestly. Fiction focused on sustainability can often shy away from the darker sides of life, instead coming across a little safe and sheltered. With a romantic moment involving snot and band names like Venus Gashtrap, Kern embraces the vulgarity of the human experience.

Set in an alternate universe where Al Gore won the 2001 US presidential election, the world in Kern’s novel seems greener at a glance. However, the parallels with our hellscape soon become clear. The motivation behind the changed timeline is simple: Kern is telling us that we won’t find our salvation in the same old party politics.

The story chronicles the build-up of a community who feels the same way. It all begins at The Lab, a warehouse converted into an anarchist community space where people live beyond the confines of regular society. Of course, not quite—The Lab is owned by Fish, a multi-millionaire who just so happens to be Maddie’s boyfriend. That, as you can imagine, sparks a lot of interpersonal conflict with the people living there, driving her story forward.

It can’t all be pinned on Fish though. Maddie spends the entire story unlearning her Christian upbringing and struggling to deal with her white privilege. Sadly, she never quite figures out how to stop putting her foot in her mouth—whether it’s a foot fetish or humiliation kink is never revealed.

Nonetheless, choosing Maddie as the protagonist was a great decision. Through her, Kern shows us that people are complicated, influenced by an upbringing they can’t control, and that expecting perfection as an entry point to a movement is a terrible idea. Like the shit-stained toilet, Maddie’s ideology needed a good scrub.

The community in the story demonstrates how there’s space for everyone in a political movement. Heroes are nothing without the cowards; saints less powerful without devils to compare them to; and grunt work is just as vital to success as creative expression. There’s a pervading sense throughout the novel that you aren’t always going to like everybody in your movement or community and that’s okay.

The novel falters, at times, when it feels like Kern prioritises making a political point over telling a story. Although it didn’t bother me too much, as I felt the sermons worthwhile, I can imagine it being a bit of an issue for other readers. The personal carbon credits system could have done with a more pointed critique, too; aside from some brief commentary on how rich white folks can game the system, I was left wanting more.

The approach to veganism also had me narrowing my eyes at points. Most of the meals associated with pleasure are meat-heavy, whereas those surrounded by a feeling of necessity tended to be plant-based. In one case, characters “settle” for a vegan pizza because they don’t have the carbon credits for meat. A different character, assumed to be vegan, suddenly decides to eat meat when there are carbon credits available.

I don’t expect every character, or even any, to be vegan. When the implication is that a life without meat is devoid of palate pleasures, or that vegans are waiting for any opportunity to drop the act and devour meat, it does, however, feel like the novel is reinforcing negative misconceptions about what veganism is and the people who follow it. To be fair to Kern, I find this issue is pretty widespread in speculative fiction.

Those are, however, small critiques in the grand scheme of what is now one of my favourite novels of its kind. Through Maddie’s story of ups and downs, Kern manages to deliver the key message of the novel: those of us alive today probably aren’t going to live in the world we so desperately want to create, and that’s why we must find joy in the struggle itself.

While that might sound sad for some, I find it a pragmatic message tinged with hope. As Maddie tells us at one point: “I have tasted a free world a few times now, and I crave another bite.”

Member discussion