What if dinner was public infrastructure?

Written by Jack McGovan / Edited by Libby Langhorn & Ruxandra Grecu

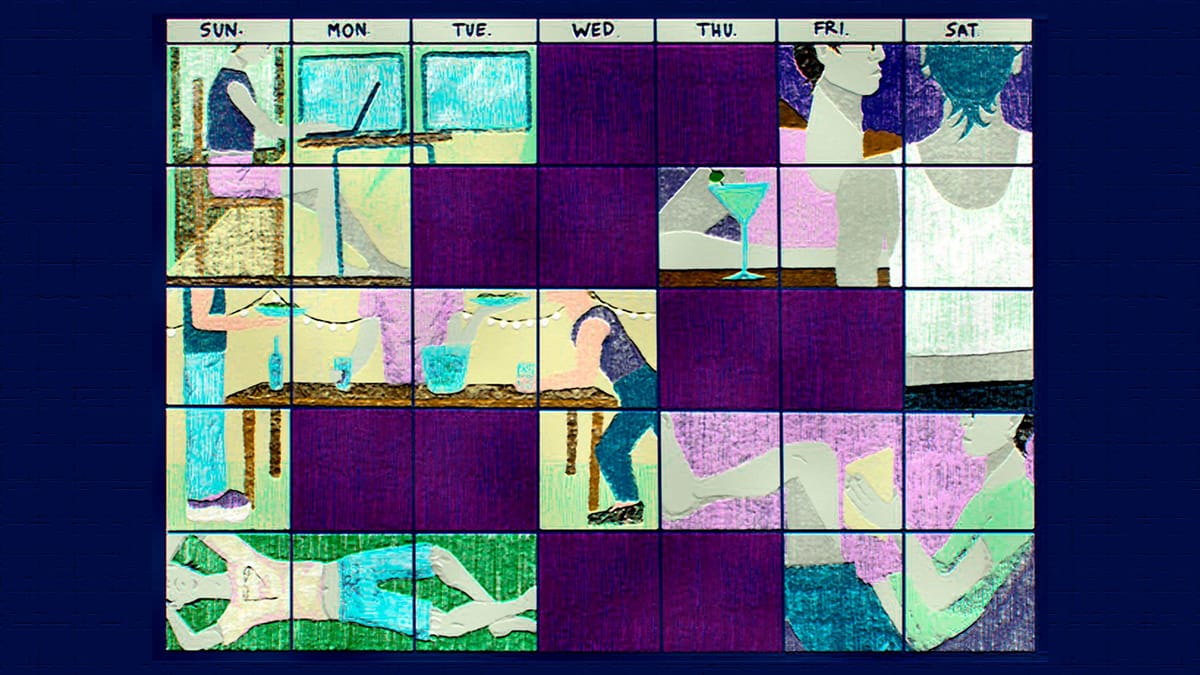

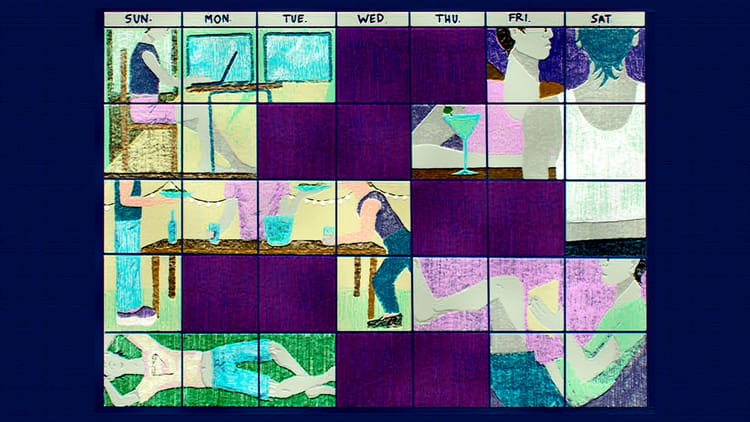

A universal student experience, often replicated after graduation, is one of having virtually no money. That’s why me and my university friends met every Sunday evening at the free community dinner. School desks inscribed with lewd drawings were pushed together like a game of Tetris to create larger tables, and people from all over the city exchanged stories about their lives and, on the odd occasion, numbers too.

When the bell tolled, everybody stood in line for the accommodatingly vegan-vegetarian buffet. The entire operation was run by volunteers. Some picked up leftover produce from the market in the town centre the day before, while others helped turn those ingredients into entreés for attendees. My favourite role was helping to clear the buffet by eating any leftovers.

Similar community dining experiences are growing in popularity across the world. In 2022, the UK’s largest community dining organisation, FoodCycle, served nearly 500,000 meals to 62 communities. The Garnethill Multicultural Centre in Glasgow hosts three different community dining experiences a week, one specifically for asylum seekers and another for the elderly. Last month, a restaurant with a sliding scale model opened in New York, USA, with cheaper meals offered to those living in the local area.

The idea of people coming together to eat might seem like a wonderful idea on the surface, but it’s also a response to something more sinister. One in ten people in the EU are unable to afford a proper meal every second day, and a third of children in the UK live in homes where there is not enough access to healthy and nutritious food. As people can’t afford basic nourishment, restaurants, too, are struggling with people no longer able to afford the experience of eating out.

While charity or pay-what-you-can models offer a way for the needy to eat, they’re a symptom of a failure in social policy. That’s why the food charity Nourish Scotland are pushing for the reintroduction of public diners to Scotland: diners subsidised by the state to provide affordable, nutritious, and filling meals that are accessible to everyone regardless of their financial status.

“There's an element of universality, dignity, and quality that comes with something being a public institution or a part of public infrastructure,” said Anna Chworow, deputy director at Nourish Scotland. “Which is not always present when you're talking about a voluntary initiative, soup kitchen, or a community meal.”

The movement behind public diners has already gained some traction. When Nourish Scotland published a report on public diners last year it received cross-party support on a motion in the Scottish Parliament from four MSPs. The charity announced in the summer that they’re involved in a research project testing pilot diners, expected to be opened in summer 2026, in Dundee and Nottingham.

Public diners already have a history in the UK, where so-called British Restaurants offered places to eat during the wartime period of the 20th century. At their peak, there were 2000 situated across the UK, all of which were subsidised by the government. For comparison, there are around 1450 McDonalds in the country today. “Before we had a national health service, we had a national restaurant service,” said Chworow.

An exhibition by Nourish Scotland demonstrating the history of British Restaurants, and how similar concepts exist in countries like Poland, Turkey, Mexico, and Singapore, is currently travelling around Scotland to raise public awareness. “We somehow seem to think, ‘Oh, no, the state couldn't do that’, and when you say, ‘No, actually, it has done that—and within our living memory’, it just allows people to go, ‘Oh, maybe we could do this again’,” said Chworow.

Chworow didn’t even realise she had personal experience with public diners until scouring the Polish government’s financial records as part of her job. She noticed the name of a restaurant—a milk bar—she’d often eaten at while growing up in Poland, but had never realised the “good honest food” her mother had often sent her to eat had been state-subsidised. “It's just a lovely testament to how embedded [milk bars] are in the infrastructure of the country,” she said.

Access to proper nutrition, however, isn’t the only issue when it comes to food. Over a quarter of global greenhouse gas emissions come from food production, with meat especially bad for the environment. Guidelines published by world-leading experts on health, sustainability, and social justice emphasise “a plant-forward diet where whole grains, fruits, vegetables, nuts, and legumes comprise a greater proportion of foods consumed” for the best human health and sustainability outcomes.

As public diners would be state-subsidised, there could be national guidelines on how to encourage people to make healthier, more sustainable choices. Small interventions like putting plant-based options first on menus or providing information on the climate impacts of food can nudge people to choose more sustainable meals. The report published by Nourish Scotland found that public diners could act as a model for how to make tasty food without focusing on meat.

"You can see it from a feminist perspective as well, I think, [to] massively alleviate the pressure on women in the home to do all that free, unpaid labor [of cooking]" — Benjamin Selwyn, professor of international development

It’s only because of my friends, many of whom I attended the Free Café with, that I learned to cook vegan meals properly. Although somebody should be at The Hague for what was slopped onto my plate at school in the UK, and I sometimes question if my mother ever truly loved me based on the meals she served, a lack of imagination is a big factor limiting dietary change. Without a herbivorous community to help me, I’d have still thought of vegan food as salads without meat and not known what a lentil was or that tinned beans didn’t have to come in a tomato sauce.

More broadly, public diners could be a guiding light for a better food system. In a piece for The Conversation published late last year, Benjamin Selwyn, professor of international relations and international development at the University of Sussex, wrote: “subsidised community restaurants could serve seasonal dishes made with locally grown plant-based food, produced on farms that encourage wildlife through widespread tree cultivation, the use of cover-crops, and improvements to soil health.”

Democratic input would also be important to make public diners work. Different demographics have cultural practices that should not only be reflected in what food is served, but also how it’s served. In places with large Muslim communities, for example, public diners should be accessible after sunset during Ramadan. Public diners could also act as a place of cultural exchange, where those from different backgrounds meet and explore cuisines from all over the world.

“A public diner in Glasgow looks very different from a public diner in the middle of Fife because the demographics are different,” said Chworow. “I don't think that the diners would be successful unless you embrace and enter into a dialogue with the customers who would be eating there.”

Selwyn agrees with Chworow that public diners need to be democratic institutions. He said public diners could “shift the balance of power a little bit against capital” and “empower workers by making them less market dependent,” meaning they wouldn’t have to rely on an income as much as they do now to eat. “It would be about changing society in a meaningful way rather than just providing something that people need,” he said.

He believes that trade unions and other collective organisations will play a big role in ensuring whether these institutions are built. “You can see it from a feminist perspective as well, I think, [to] massively alleviate the pressure on women in the home to do all that free, unpaid labor [of cooking],” he said.

At their peak, there were 2000 public diners situated across the UK, all of which were subsidised by the government.

With all of the different facets of public diners taken into account, Chworow said it’s important that the right balance is struck between them. While public diners could help to meet climate goals, for example, that shouldn’t be their main focus as it comes with certain connotations that could turn people off.

But if public diners are so great, why did they disappear in the first place? Bryce Evans, a professor of modern world history at Liverpool Hope University who has written a book on the history of British Restaurants, told Sower in an email there were three main reasons they were shut down: the political will to keep them disappeared after the war ended; private retail trade rallied hard against state-subsidised dining and urged a return to the free market; and the central government cut funding.

The UK government recently announced it would hike fees for students, and this week the US government cut funding for those unable to afford food, demonstrating how the Western world is moving away from state-supported necessities. If the political will to keep public diners didn’t exist in the post-war period, when the government built up huge social safety nets through the construction of council houses and free national healthcare, what chance is there in today’s world?

When I think back to my time at the Free Café, the people who attended were largely the same demographic: white, middle class, and environmentally conscious. The beauty of a public diner would be the universality—that, in theory, you could be seated next to somebody who depended on the state for survival, and on the other side could be somebody who wasn’t King Charles. Although, Charles aside, it’s a lovely vision for the future of food that centres community spirit, the concept might not translate as well as you might hope into the public consciousness.

People who eat more frequently with others are more likely to feel happy and satisfied with their lives, yet most meals eaten aren’t a community experience. In many cases, community meals are associated with charity, as, sadly, they often are somewhat charitable in nature. During the Covid pandemic, for example, small community food organisations stepped in to help people who, for financial or health reasons, could no longer get their own food.

Adele Wylie, a PhD student at the University of Reading, studied how the pandemic shaped people’s access to food. After seeing how widespread food poverty was, she decided to organise a pop-up mimicking the public diner concept in Manchester in February this year. Although Wylie said there was a lot of enthusiasm to get the concept off the ground from those who attended, she added it could take a long time for people not to associate such spaces with charity. “There needs to be some consideration about how to attract people to come,” she said.

Jill Muirie, public health programme manager at the Glasgow Centre for Population Health, has attended events on public diners and can see the public health benefits of the state providing good, nutritious, and affordable food. At the same time, she’s not sure they’d be as universally appealing as you’d want them to be. “I think there's probably quite a lot of work to be done to develop understanding of that public diner concept, but also to find suitable funding for it at the moment,” said Muirie.

"Before we had a national health service, we had a national restaurant service" — Anna Chworow, Nourish Scotland

Financing a complete overhaul of how food is distributed is already a gargantuan task, but the idea of building public eating establishments across the country that have mass appeal at a time where everything is so polarised feels Sisyphean; public diners are, unfortunately, fighting both a rhetorical and financial uphill battle. There is, however, another approach that has already found some success.

The CanTeams project hosts community dining experiences at schools across England. So far, the project has served over 3000 people at over 50 events. “We're trying to turn schools into community hubs, and using activities and nutritious food to do that,” said Jonathan Harper, CEO of Future Foundations, the organisation behind CanTeams. “If you have a young person performing, singing, or doing something… [that] can help catalyse communities coming in.”

Although the project primarily focuses on school children and their immediate families, there have been events involving pensioners or those in care homes. Harper told the story of one old lady who said she was scared of young people and therefore didn’t take the bus in the afternoons, who, after sitting side by side with teenagers and breaking bread with them, felt safe. In the future, he wants to create events where the wider community can come in to eat after the children leave.

With the state having left a potato-shaped vacuum in society, Harper believes it’s up to citizens and communities to act. Although he’s very supportive of public diners and would welcome them with open arms, he also thinks that something like CanTeams would be more palatable in the current political climate. Not only does the project use existing infrastructure by taking place in school cafeterias, and therefore doesn’t have the same start-up costs as public diners, it doesn’t rely on state funding at all—though, he added, it would be very welcome.

The project has made its mark by relying on philanthropic funding. In the future, Harper hopes to get more private sponsorships and test pay-what-you-can models to make the concept self-sustaining. The Long Table in Gloucestershire, UK, has a pay-what-you-can model and has made enough money to employ 22 part-time and full-time members of staff on a real living wage, showing that it's entirely possible. Based on the success of CanTeams so far, Harper was invited to join the advisory board of DISHED, the overarching project responsible for the public diner pilots in Dundee and Nottingham.

Relying on the private sector comes with its own problems. History, defined as yesterday or earlier, shows us that private interests can't be trusted with assets—unless you enjoy rivers filled with human faeces, overpriced trains with horrible service, and school meals being snatched from children. Building the future of food on the whims of private individuals, companies, or organisations isn’t solid ground for important infrastructure, even though, admittedly, I do understand Harper’s point that CanTeams feels like a more politically-palatable option.

In response to the idea that the government is unlikely to support public diners, Chworow said she believes they will have little choice as poor diets now rival smoking as a leading cause of death. She added that Scotland and England have different political contexts, too, and that public diners would most likely first be adopted by progressive governments in Scotland and Wales, as well as cities like London and Manchester. She added that a similar rollout of public diners happened in Mexico and with infrastructure like the National Health Service and libraries in the UK.

Yet even if the rollout of public diners did feel truly impossible, that shouldn't stop us from demanding them anyway. During times of feudalism, the idea of democracy would have been unthinkable; before workers secured the right to a five day week, leisure time would have been an activity for the wealthy; and Frodo and the rest of the fellowship would have never made it to Mount Doom and destroyed the ring if they were too afraid to take the journey.

The ideal scenario would be public diners and CanTeams being publicly funded concepts spread across the world: one a place of democracy where people take more control of the foods that they eat, and another that builds intergenerational bridges and treats young people like active participants in society. Both can only contribute to strengthening our bonds with those in our communities, building in more resilience against fascism.

One old lady said she was scared of young people and therefore didn’t take the bus in the afternoons. After sitting side by side with teenagers and breaking bread with them at CanTeams, she felt safe.

In the meantime, CanTeams' approach is a great way to foster more consciousness around community eating, especially because children will grow into the next generation of voters; the more people care about community meals on a broader scale, the more likely they are to get sustained funding from the government.

The majority of people I'm still in contact with from university are those I attended the Free Café with. While it's possible they were already the people I would have remained close to following graduation, there's something there to be said about the power of food bringing people together. Many of the relationships I've built today wouldn't exist without food and the way I interact with it.

Public diners and other forms of community eating like CanTeams can help give people access to climate-friendly, nutritious food, but they also serve as a reminder that the human experience is one of community. To adapt a popular refrain, the quickest way to a person's heart—in this case, their empathy for themselves, the planet, and those around them—is through their stomach.

Want to make public diners a reality?

- If you're in the UK, you can reach out directly to Nourish Scotland and ask them how you can get involved. If you're a parent or teacher, you could also try get your school involved with CanTeams.

- Reach out to your MP asking them to look into the idea of public diners and support it in parliament.

- If you're outside of the UK, look to see if there are any similar initiatives going on in your country of residence.

- Start attending or organising a community meal—there's no better way to bring about community eating than doing it!

- Share this article with people who might be inspired to act, and subscribe to spread ideas like this to a wider audience!

Member discussion