Working less is the most underrated climate solution

Written by Jack McGovan / Edited by Ruxandra Grecu & Libby Langhorn

A previous employer had such faith in my abilities they made me responsible for two roles, despite, of course, only paying me for one. When I failed to meet their expectations of fitting 68 hours’ worth of work into the 28 I was contracted for, I was publicly flogged on the company’s Slack, a whipping boy for upper management’s failure to attract suitable talent.

I did, however, enjoy it.

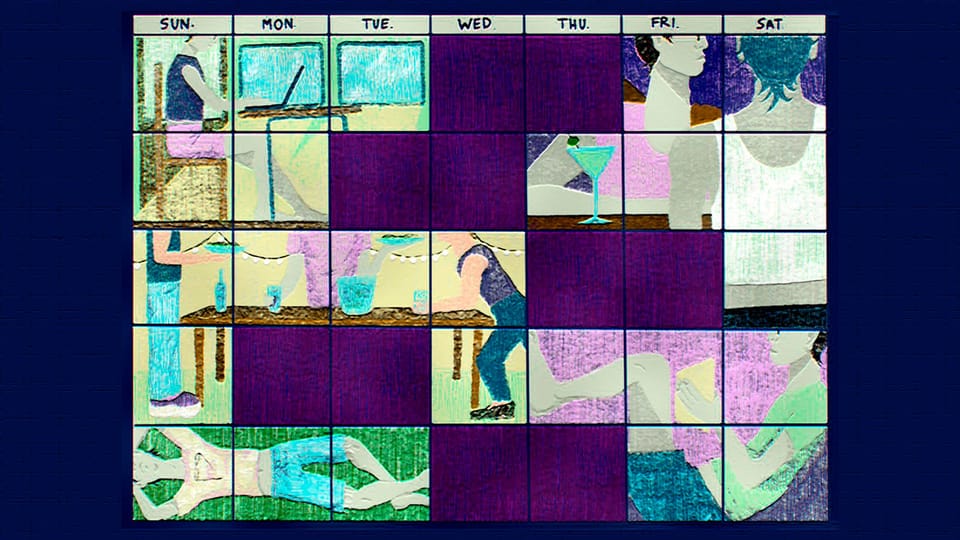

Not the flogging—though that would be on brand for somebody living in Berlin—but working reduced hours. With 3.5 days to myself every week, I maintained my work-life balance with gymnastic precision. I immersed myself in the culture of the city, while still having time to recuperate from work, late nights in the club, and the terror of living under German bureaucracy.

The same couldn’t be said for my colleague who worked a 40-hour week. His attempts to juggle a hostile working environment with the life he wanted to lead on the outside could most gracefully be described as unsuccessful. After months of struggle, he ended up on sick leave due to burnout and eventually lost his job.

No, it (probably) wasn’t a skill issue: a survey of self-assessed burnout levels found that 59 percent of Europeans had experienced feelings of burnout, often felt like they were on the verge of burning out, or had actually burnt out. A 2023 report found that shifting to a four-day week reduced feelings of burnout for 71 percent of the 2900 workers questioned.

Working fewer hours has other benefits, too. Longer working weeks are associated with higher emissions from commuting and the consumption of “ready-made meals, weekend vacations, household equipment, and van-delivered items bought online.” Data analysed from 29 high-income countries over a 37-year period found countries with longer working hours consumed more resources, emitted more carbon, and had a larger ecological footprint.

A 2023 report found that shifting to a four-day week reduced feelings of burnout for 71 percent of the 2900 workers questioned.

It’s ironic, then, that the idea of a four-day week seems to be spreading like wildfire. Spain, Portugal, and Germany are testing the idea of a four-day week. Belgians can already condense their 40 hours into four days if they wish, and 90 percent of Iceland’s population has reduced working hours. Companies in New Zealand and Japan have also tested the idea. In March last year, Bernie Sanders put forward a bill for a four-day week in the US Senate.

The campaign in the UK also reached a landmark earlier this year when the 200th company signed up for a permanent four-day week with no loss of pay. Given the benefits to people and planet, it seemed like a no-brainer that climate organisations, who so often espouse the need for system change and a new way of living, would make up a decent chunk of those signed up to the campaign.

Of the 200 companies, however, only seven had some relevance to environmental issues. Many heavyweights in the field, like Greenpeace, WWF and Client Earth, were notably absent. In a four-day week pilot in Germany, only one of the 45 businesses who took part—a solar panel installation company—had any kind of climate connection.

Joe Ryle, campaign director at the 4 Day Week Foundation, UK, said the idea has largely been ignored by the climate movement. In 2021, his organisation commissioned a report on the climate benefits of the four-day week, which failed to get traction in environmental circles. “I think quite often environmental activists have lost sight of actually the wider vision of the society we want to build,” he said.

A shorter working week is about “creating a more positive society” where “we have more free time” and the “time to engage in more environmentally sustainable behaviours,” he added. “It could be a huge missed opportunity for the climate movement if they continue to ignore the benefits.”

I always say that freelance journalism is my least worst option for earning money and surviving in this world. I genuinely love it, but would I rather sit behind my desk for the majority of the week than cook and share meals with loved ones, laze down by the canal with my nose in a book, or go out dancing? It depends on the weather, music or story, but my preferences lean towards the latter pursuits.

Humans are social creatures. Many of the activities we enjoy the most are those rooted in communities outside of the workplace, such as playing with children, performing religious acts, or roasting our closest friends in jest. We spend so much time on the clock, however, that it becomes impossible to engage with everybody we’d like to in a meaningful way. Not only do our personal relationships suffer, the social fabric itself seems to be falling apart.

Over two-thirds of people said they would spend more time with friends and family if they worked a four-day week. Over half said they’d spend more time home cooking, and a quarter said they’d do local volunteering. Research suggests that when people have more time off, they tend to spend it doing “soft” activities like reading, playing, or exercising, wink wink.

“It could be a huge missed opportunity for the climate movement if they continue to ignore the benefits" – Joe Ryle, 4 Day Week Foundation

Michael Weatherhead, co-founder of the Wellbeing Economy Alliance (WEALL), has used his extra time off to volunteer as chair of the Woodlands Community Development Trust, Glasgow, since his organisation moved to a four-day week. With Fridays free, he’s been able to dedicate more time to the charity than he otherwise would have. “I feel I can bring other skills from my day job in support of the organisation—be that developing visions, strategies, [or] supporting with fundraising,” he said.

WEALL is one of the seven organisations with a climate link accredited by the 4 Day Week Foundation. Others include Friends of the Earth UK (FOE), the Scottish Green Party, and Opportunity Green. European Greens adopted a resolution for a four-day week in the summer of 2021.

Weatherhead and his colleagues have worked a 32-hour week from Monday to Thursday with no loss of pay since last year. With fewer hours available during the week, the transcontinental team streamlined their workflow and decided to cut down on the number of meetings—arguably the biggest benefit of a four-day week so far.

Adrian Cruden, head of people at FOE, doesn’t work on Mondays and uses the time to go walking when it’s quieter, to visit friends, and to work on his writing. The four-day week at FOE has meant no loss of pay with other positives, too. “It hasn't led to any reduction in output,” said Cruden. “We've seen a bit of a decline in sickness absence, especially around mental health and stress.”

A report focused on the outcomes of a four-day week pilot in the UK found that the vast majority of participating organisations were satisfied that business performance and productivity were maintained. When Microsoft implemented a four-day week in Japan, productivity even increased by 40 percent.

One unexpected consequence is the “huge increase” in job applications from qualified candidates. “From the point of view of other employers, I would strongly recommend it as certainly being something which helps very much in your recruitment,” said Cruden.

Employees at FOE get to decide which day they want off as the organisation is still active from Monday to Friday. They have people working in the political or legal sector who can’t, for example, say they’re not available to go to court on specific days. Well, they could, but that probably wouldn’t help their aims of protecting people and planet.

“We are still functioning within an economy and a society which is geared to very different things,” said Cruden, and so what we would like to do versus what we can do is very different. He said many voluntary organisations rely on funding that might come with specific stipulations that prevent a switch to a four-day week.

One unexpected consequence [of a four-day week] is the “huge increase” in job applications from qualified candidates.

In 2020, Greenpeace Aotearoa shared an article on their website which discussed the environmental benefits of moving to a four-day week, yet the organisation hasn’t implemented it company-wide.

“We don't see a four-day working week being a good fit for Greenpeace because a lot of our work is responsive to what happens outside the organisation and that requires many of our staff to be available [five days a week] and in some cases more,” said Moira Neho, organisational director at Greenpeace Aotearoa, in an emailed statement.

Neho added that Greenpeace never accepts funding from governments or businesses to protect their independence, and so the work they do relies on supporters. The organisation is therefore keen to be as effective as possible to honour their trust.

“We do have a hybrid working arrangement however which reduces commuting and emissions as well as helping our staff balance their lives by working at home [three days a week] if they wish. And we allow some staff to work four day weeks or nine-day fortnights on a case-by-case basis,” she added.

Paul West, senior scientist at climate solutions organisation Project Drawdown, said in an emailed statement that while there are numerous reasons to move towards a four-day week, he isn’t sure climate is one of them, as emission reductions depend on what people do with the time off.

“For something to be a climate solution, it must materially reduce emissions by cutting them at the source or removing them from the atmosphere,” he said. “Emissions may be reduced from commuting [in a four-day week], for instance, but those gains can be easily offset or emissions increased if they lead to more three-day trips, especially if they travel by plane.”

A master’s thesis published last year by Max Collett, a student at the University of Oxford’s Smith School of Enterprise & Environment, found that leisure travel was the second most common thing people on a four-day week spent their money on, as the extra day off made intercity and international travel more worthwhile.

“Emissions may be reduced from commuting [in a four-day week]... but those gains can be easily offset or emissions increased if they lead to more three-day trips, especially if they travel by plane" – Paul West, Project Drawdown

The report commissioned by the 4 Day Week Foundation concluded that to ensure a four-day week brings the promised environmental benefits, wider policies would be necessary to “promote a large-scale shift from high carbon consumption towards a more convivial, lower-carbon society.”

One recommended policy is improving the public provision of free and low-carbon leisure at the local level. Imagine, for example, fully-funded sports centres, play areas for children, and accessible music facilities for all, as well as regular festivals facilitating cultural exchanges and the consumption of climate-friendly foods.

After the second public flogging at my four-day week job, I’d had enough and moved on to a two-day week job instead. Media reports of a strange virus dominated headlines when I interviewed for the role, and by the time I clocked in for my first shift, the aubergine-purple walls of my new room had become a cage, the backdrop for the next step in my career.

At first, the setup worked well. I was able to try and break into the journalism industry without worrying about making rent, all while being able to take a nap whenever I wanted. After two years working the job, however, it began to weigh heavily on me. Although I had more time to focus on my writing, and the people were infinitely nicer to me, there was something so soul-destroying about those eight-hour days.

Bullshit Jobs by David Graeber explained why. I had what he described in the book as a duct-taping job: I existed only to correct the mistakes of an algorithm. The company made money by charging for job adverts on their platform, and it was my task to format and tag them because it was cheaper than fixing the algorithm. (Eat your heart out, ChatGPT.)

“In the year 1930, John Maynard Keynes predicted that, by century’s end, technology would have advanced sufficiently that countries like Great Britain or the United States would have achieved a fifteen-hour work week,” wrote Graeber in the book. “Instead, technology has been marshalled, if anything, to figure out ways to make us all work more. In order to achieve this, jobs have had to be created that are, effectively, pointless.”

The book referenced a YouGov poll which found that 37 percent of respondents said their job didn’t make a meaningful contribution to the world. “The moral and spiritual damage that comes from this situation is profound,” wrote Graeber. “It is a scar across our collective soul.”

I’m lucky enough to be somebody who finds his work fulfilling. But it comes at a price, or, more specifically, a lack thereof: earning a living as a freelance journalist is nigh on impossible these days without supplementing your income with other kinds of work. Similar conditions exist in other creative fields, particularly as generative “AI” cuts into workforces.

It’s not just creative fields under threat. In the UK, two thirds of nurses said the pressure of their job has become too much amidst staff shortages, with almost half thinking of quitting. Low wages and anxieties are a big driver of the crisis, even though the majority of nurses still consider the job to be a rewarding career.

I think we can all agree that creative or care work is more fulfilling than fixing the mistakes of an algorithm, yet it is specifically the former roles that are harder to earn a reasonable living from. By cutting down the total hours we work as a society, we could instead fairly distribute the meaningful, necessary work amongst ourselves.

Working less is also a popular policy idea: around 67 percent of workers said they'd sacrifice some of their salary for a four-day week. Campaigning on a platform where workers wouldn't have to lose income seems like an issue we could all coalesce around, restoring a sense of class consciousness not felt for decades. That could, in turn, be used to deal with other labour issues like "AI" or falling living standards.

Yes, it’s important that we stop emitting carbon. But with so many people burnt out and unfulfilled, there's a chance here to create a broader narrative of how we can all work less, take our free time back from the ruling classes, and in the process reduce emissions—make everybody happy, oligarchs aside.

There are also options to push beyond a four-day week. Workers could receive community or care days every year alongside their paid annual leave, giving them time to engage in community projects or to care for their children, relatives, or chosen family. From a climate perspective, maybe those who travel internationally for work could be rewarded with days off for taking the train, as an incentive to avoid aviation.

A four-day week, or even fewer working hours than that, isn’t going to solve all of our problems. It could, however, be a big step forward as part of a wider vision and package of policies that get us more in touch with our communities and ourselves. Let’s not miss the forest for the trees, otherwise we might realise a little too late that we can’t stop the wildfire.

Want to make a four-day week a reality?

- Ryle from the 4 Day Week Foundation said the best thing you can do to make a four-day week a reality is organising in your workplace. There's a practical step-by-step guide on their website for how to do that: https://www.4dayweek.co.uk/advice-for-workers.

- You could join a trade union for support. In the UK, for example, UNISON have published a bargaining guide for getting a four-day week in your workplace: https://www.unison.org.uk/content/uploads/2024/11/Four-Day-Week-Guide-v6.pdf.

- If you're not in the UK, you can look for a campaign in your country and reach out to the people there to ask for advice. There are trade unions across Europe, for example, who are fighting for a four-day week.

- Look for the political parties in your region who have committed to a four-day week and get involved with them.

- Share this article with people who might be inspired to act, and subscribe to support ideas like this!

Member discussion